By Daniela Silva-Rodriguez Bonazzi

Asociación Panamericana de Horticultura Terapéutica y Social (APHTS)

Read the article in Spanish here.

I. Introduction: Green Spaces as Sanctuaries for Healing

In an age marked by ecological degradation, cultural homogenization, and rising mental health challenges, green spaces have reemerged as vital sanctuaries for healing, learning, and connection. Among these, hortus medicus — gardens dedicated to medicinal plants — hold unique significance. Historically rooted in the practices of ancient civilizations and monastic traditions, these gardens are now being reimagined as dynamic spaces where horticultural therapy, cultural dialogue, and ethnobotanical education intersect, where illness and recovery unfold between humans and nonhumans.

Botanical gardens serve as vital centers for scientific research, conservation, and recreation. They offer a wide range of environmental benefits, including the preservation of biodiversity, educational outreach, and cultural enrichment. This article explores the evolving role of hortus medicus as therapeutic landscapes that nurture body, mind, and community through the cultivation and celebration of medicinal plants.

II. Hortus Medicus: A Historical and Contemporary Framework

The concept of the hortus medicus can be traced back to early civilizations where healing gardens played integral roles in both health care and spiritual life. In medieval Europe, monastic communities cultivated walled herb gardens as part of their medical and religious practice. The Islamic world developed sophisticated medicinal gardens in conjunction with hospitals, emphasizing the harmony between nature and healing. In Asia, traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine have long relied on curated plant collections for diagnosis and treatment.

By the Renaissance, these gardens were institutionalized within universities as botanical gardens, serving both scientific inquiry and pharmacological training. Today, hortus medicus are reemerging in various forms: as public botanical gardens, community herbal gardens, and therapeutic landscapes in healthcare settings. They continue to serve as bridges between historical wisdom and contemporary wellness needs.

Benefits of Urban Ethnobotanical Gardens & Medicinal Plant Integration for Prevention

Establishing an ethnobotanical garden within a city offers a multitude of benefits for both residents and visitors. These carefully curated green spaces contribute significantly to education, conservation, community well-being, and economic vitality.

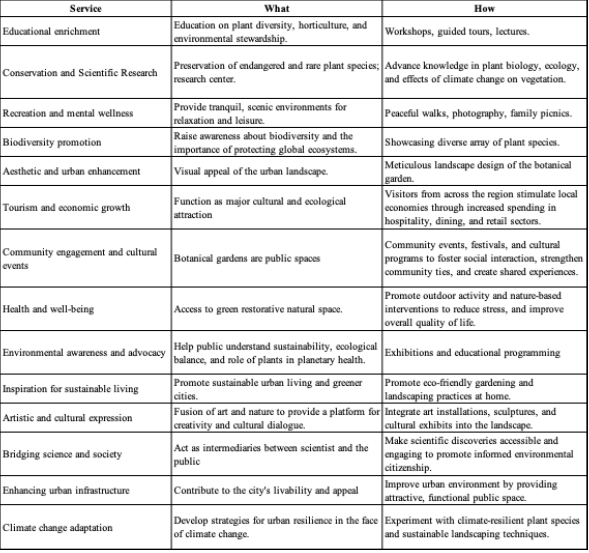

Cultural ecosystem services can be obtained through diverse actions, mentioned in the following table.

Ethnobotanical gardens can form collaborative partnerships with health providers and urban planners to promote community health. While these efforts may not generate direct income for the gardens, they can lead to broader societal benefits, such as improved public health and reduced costs in publicly funded healthcare systems, all while maintaining the core functions of a botanic garden.

The term medicinal plants was first formally introduced in 1967 in the context of research on hallucinogenic species. Medicinal plants are defined as members of the plant kingdom whose parts, such as flowers, leaves, stems, roots, fruits, or seeds, are used directly or as part of medicinal preparations to treat or prevent disease. The knowledge of their therapeutic properties represents a critical resource for preserving both biological and cultural diversity among different ethnic groups (Heinrich et al., 2017).

Since pre-Hispanic times, indigenous healers have utilized medicinal plants as a cornerstone of traditional knowledge and healthcare practices (Heinrich, Ankli, Frei, Wiemann, & Sticher, 1998). Their effectiveness is largely attributed to secondary metabolites with pharmacological activity, many of which serve as the basis for modern therapeutics including antitumor, antiviral, antiepileptic, antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic agents (Alonso-Castro et al., 2011; Le Rhun, Devos, & Bourg, 2019; Sharma et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019).

The Economics of Medicinal Biodiversity

Current data indicate that Earth is home to approximately 391,000 vascular plant species, with at least 35,000 recognized for their medicinal potential. Notably, 25% of the active compounds used in pharmaceuticals are derived from plants, and an estimated 80% of the global population still relies on traditional herbal remedies for primary healthcare (García de Alba García et al., 2012; Kew et al., 2016). The use of plant-based treatments has grown significantly in the last decade (Ekor, Adeyemi, & Otuechere, 2013). In 2015, the global market for medicinal plants and plant-derived pharmaceuticals was valued at $25.6 billion and was projected to increase to $35.4 billion by 2020 (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew et al., 2016), reflecting growing international interest in plant-based health solutions (Alonso-Castro et al., 2017).The economics of medicinal biodiversity reinforce the urgency of integrating plant-based prevention into health systems (Singh, A. 2016).

A review carried out by Salmerón-Manzano et.al.,2020, outlines how traditional medicinal plant use forms the basis for many modern pharmaceuticals. It highlights the value of preserving ethnobotanical knowledge as a preventive resource and drug discovery source.

Rigorous Scientific Validation Needed

However, despite this widespread use, many medicinal plants still lack rigorous scientific validation regarding their chemical composition, pharmacological efficacy, and potential toxicity (Alonso-Castro et al., 2018). Even in urban settings where access to conventional healthcare has improved, medicinal plants remain a vital part of healthcare for many populations (Alonso-Castro et al., 2012; Juárez Vázquez et al., 2013).

Medicinal plants are foundational to traditional primary healthcare and preventive medicine in a wide global context, from indigenous communities to modern drug discovery. Ethnobotanical gardens serve as vital bridges by preserving plant species and traditional knowledge, as well as enhancing community access and education regarding preventive health. The integration of medicinal plants into formal health systems through the creation of ethnobotanical gardens aligns with global public health strategies (like primary health care -PHC) and yields cultural, financial, and ecological benefits.

Medicinal Plants in Disease Prevention

Misganaw, W. et.al., 2025, wrote about the important role of medicinal plants in disease prevention strategies supporting maternal and child health, nutrition, common illnesses, endemic diseases, mental/oral health, and serve as essential drugs in primary health care (PHC). Medicinal plants naturally fit into established prevention strategies but require formal recognition and coordination within health systems.

A case‑study‑based article, Community Gardens: Cultivating Medicinal Plants for Local Disease Prevention, by Kintuza Lumwako Tebulo, 2025, examines how integrating medicinal plants into urban community gardens contributes to disease prevention, holistic wellness, and public health promotion. It emphasizes community involvement, sustainability, and education as core to success.

A study by Misganaw et al., 2025, documents over 112 plant species used locally for human and livestock health, underscoring the crucial role of traditional phytomedicines in primary healthcare, especially in underserved rural areas. It calls for conservation and sustainability to support ongoing health benefits.

How Remedies Integrate into Community Well-Being

In 2023, Bastidas-Bacca et.al., catalogued plant species used culturally for disease prevention and mitigation of chronic conditions in the Colón Putumayo Community in Colombia, through interviews and community data. Indigenous cosmology and plant cycles frame how these remedies are integrated into community well‑being.

Studies from Ethiopia (Misganaw, W., 2025; Awas, T., 2022) show that over 80 % of rural communities still depend on herbal medicines for primary care, underscoring the need for formal capture of this tradition within health policy. Research highlights how traditional phytomedicines are crucial for affordable and culturally appropriate care. It advocates for integrating traditional medicine into formal healthcare systems, showing links between ecosystem health, cultural practices, and public health outcomes.

III. Medicinal Gardens and Horticultural Therapy

Horticultural therapy (HT) involves the engagement of individuals in gardening and plant-based activities facilitated by trained professionals to achieve therapeutic goals. Medicinal gardens are particularly well-suited for HT due to their sensory richness and symbolic association with healing. The act of planting, tending, and harvesting medicinal herbs like lavender, chamomile, or lemon balm can offer emotional grounding, stress reduction, and a sense of purpose.

Clinical studies have shown that access to nature, especially through interactive green spaces, can alleviate symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and cognitive decline. In settings ranging from psychiatric hospitals to rehabilitation centers, hortus medicus provide structured and meaningful engagement, empowering individuals through nature-based care.

Perceived Psychological Benefits

A study conducted at the Government Botanical Garden in Udhagamandalam, Tamil Nadu, India (Sasmitha & Arunachalam 2017) examined the perceived psychological benefits experienced by long-term visitors. The findings highlight the significant therapeutic value of botanical gardens, particularly in enhancingpsychological well-being. Among the perceived psychological benefits experienced by visitors were high levels of relaxation, peace of mind, and stress relief; aromatic plants, and colorful flowers contributed to feelings of freshness, emotional rejuvenation, and joy; engagement with the green space improved mood, reduced anxiety and sadness, and promoted a sense of freedom and satisfaction; gardening activities were associated with increased self-esteem, independence, and a sense of accomplishment; contact with nature was believed to enhance memory, patience, and positive thinking. The study concludes that botanical gardens serve as important spaces for therapeutic horticulture, offering non-clinical yet impactful benefits to mental health and general wellbeing.

IV. Cultural Exchange Through Medicinal Gardens

Medicinal gardens can also serve as vibrant spaces for intercultural dialogue. Every culture has its own pharmacopeia, a body of traditional knowledge about plants and their healing properties. By including plants and narratives from diverse traditions, hortus medicus become platforms for sharing and honoring this knowledge.

In multicultural urban areas, ethnobotanical gardens have been used to bring together indigenous, immigrant, and local communities to co-create healing spaces. These gardens often include interpretive signage, storytelling circles, and workshops led by traditional healers. Through these activities, communities not only preserve endangered knowledge systems but also build empathy and respect across cultural lines.

V. Raising Awareness of Medicinal Plant Use and Conservation

Beyond their therapeutic and cultural functions, hortus medicus play a vital educational role. They offer immersive learning environments where visitors can explore the medicinal uses of plants, their ecological roles, and issues surrounding their conservation.

Many medicinal species face threats from habitat loss, climate change, and overharvesting. Gardens that cultivate and display these plants contribute to their preservation while fostering a conservation ethic among the public. By showcasing both the benefits and the vulnerabilities of medicinal flora, hortus medicus nurture informed, responsible engagement with nature.

VI. Designing Ethnobotanical Green Spaces: Principles and Practice

Creating an ethnobotanical garden involves more than simply planting herbs. It requires intentional design that integrates therapeutic, cultural, and ecological dimensions. Universal design principles include aspects such as accessibility ensuring that paths, beds, and signage are usable by people of all abilities; multisensory engagement incorporating color, fragrance, texture, and sound to enhance therapeutic impact; cultural inclusivity curating plants from various healing traditions and collaborating with cultural practitioners; educational storytelling using signs, QR codes, and installations to convey plant histories and uses.

Successful examples often emerge from partnerships among horticultural therapists, landscape architects, herbalists, ethnobotanists, and community members. The result is a living space that heals not only through its plants, but through the connections it fosters.

VII. Conclusion

In their reimagined forms, hortus medicus offer far more than collections of medicinal plants. They are sanctuaries for holistic healing, crossroads for cultural wisdom, and classrooms for ecological consciousness. As we seek solutions to modern crises in health, identity, and environment, these gardens remind us of ancient truths: that nature is medicine, that diversity is strength, and that healing grows where care is cultivated.

By supporting and engaging with ethnobotanical gardens, we invest in a future where communities thrive through shared knowledge, living traditions, and the quiet, persistent resilience of the plants that heal us.

Literature Cited

- SASMITHA and ARUNACHALAM, Therapeutic Value of Botanical Gardens and their Role in Improving the Psychological Well-being of the Visitors. Trends in Biosciences 10 (34), 2017.

- Gonzalez, M.T., Hartig, T., Patil, G.G., Martinsen, E.W. and Kirkevold, M.2009. Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: A prospective study. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 23: 312-328.

- G. Chen, W. Sun. 2018. The role of botanical gardens in scientific research, conservation, and citizen science. Plant Diversity 40: 181-188

- Misganaw et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2025) 21:31 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-025-00775-3

- Woldeamanuel MM, Geda MK, Mohapatra S, Bastia TK, Rath P and Panda AK (2022), Ethnobotanical study of endemic and non-endemic medicinal plants used by indigenous people in environs of Gullele botanical garden Addis Ababa, central Ethiopia: A major focus on Asteraceae family. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1020097. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1020097

- Kintuza Lumwako Tebulo (2025). Community Gardens: Cultivating Medicinal Plants for Local Disease Prevention. Research Output Journal of Biological and Applied Science 5(2):1-4. https://doi.org/10.59298/ROJBAS/2025/521400

- Sofowora et al. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. (2013) 10(5):210-229 http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajtcam.v10i5.2

- B. Mulhauser, E. Gaille. Citizen science in a botanical garden. Economic Botany, 78(2), 2024, pp. 150–168

- Singh et al. Role of Medicinal Plants for Health Perspective: Special Reference to Antioxidant Potential. J Chem Biol Ther 2016, 1:2 DOI: 10.4172/2572-0406.1000106

- Heinrich, M., Ankli, A., Frei, B., Weimann, C., & Sticher, O. (1998).

Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Social Science & Medicine, 47(11), 1859–1871. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6 - Alonso‑Castro, A. J., Villarreal, M. L., Salazar‑Olivo, L. A., Gómez‑Sánchez, M., Domínguez, F., & García‑Carranca, A. (2011).

Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: Pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 133(3), 945–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.055 - Alonso‑Castro, A. J., et al. (2017).

Medicinal plants considered toxic in North and Central America and the Caribbean: Ethnobotanical and toxicological review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2017, 9439868. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9439868 - Salmerón-Manzano E, Garrido-Cardenas JA, Manzano-Agugliaro F. Worldwide Research Trends on Medicinal Plants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 May 12;17(10):3376. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103376. PMID: 32408690; PMCID: PMC7277765.

- Bastidas‑Bacca, M. A., Dayve‑Bacca‑Descance, D., Guerra‑Acosta, A. del S., Perea‑Morera, E., Díaz‑Ariza, L. A., López‑Álvarez, D., & Osorio‑García, A. M. (2023). Ethnobotanical insights: Qualitative analysis of medicinal plants in Colón, Putumayo for traditional knowledge preservation. Plants, 12(19), 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193390