Springtime; the Season of Unabashed Awe

The season of Spring officially begins when the sun’s rays cross the Earth’s celestial equator. We recognize this moment in time as the vernal equinox. For inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere, reaching the vernal equinox signifies the darkest days of winter are behind us. Nature responds quickly to this celestial event as trees and shrubs break dormancy, ephemeral plants emerge from the warming soil, birds migrate north, and insects once again appear as an indication that Spring is arriving. It is truly an awe-inspiring season for anyone who takes notice. And you should take the time to notice, as evidence reveals, being in a state of awe is a very effective method to improve quality of life.

Jonah Paquette, PSYD

Awe blurs the line between the self and the world around us, diminishes the ego, and links us to the greater forces that surround us in the world and the larger universe.

Awe is a complex human emotion. It is difficult to define because awe can facilitate feelings of anger or joy, pride or sorrow, enlightenment, or confusion. One individuals’ response can be different from someone else’s, further complicating our comprehension of this enigmatic emotion. When experiencing awe an alteration in our sense of self occurs. Our focus is shifted away from a person-centric view to a broader, more expansive perspective. Awe produces the realization that we are part of something much greater than ourselves, often referred to as the “small-self perspective”. Awe triggers are found in many different forms, like witnessing acts of kindness or aggression. Awe is effortlessly found in nature, music, art, and spiritual or religious experiences.

Pursuing Awe

Reese Nelson, PhD is a horticulture professor at Brigham Young University-Idaho and a former student at HTI. In 2017, he held a small family gathering at his home to witness a total eclipse in southeast Idaho. Although he expected to be impressed by the eclipse, he was not prepared for the astounding feelings of awe that resulted. This led Reese to ask the question, “Why did I feel all these emotions simply through observation?” In pursuit of answers, he conducted a personal academic research study. He began to look for prosocial behaviors while attending sporting events or while attending a concert. He also visited natural monument sites and various National Parks searching for experiences of connection and awe.

Since witnessing his first total eclipse in 2017, Reese is now a self-proclaimed “Eclipse Chaser”. This past April, Reese and other family members traveled across the country to the Katahdin Woods and Waters Region of Maine, to witness his second total eclipse. This time he brought along knowledge and experience. Although the Katahdin Region is a vast natural space, it is short on public gathering places. Reese describes sitting at the edge of a lake with many people packed into a tight space. Yet, he articulates a shared, positive experience, or “collective effervescence” brought on by worthwhile conversations and witnessing a natural phenomenon with a group of strangers. Even the massive traffic jam that resulted after the eclipse, did not take away from the experience. When asked if he would make the effort to witness a third total eclipse (occurring in August of 2044) Reese states, “If I am able, I will be there!”

The Neurobiology of Awe

Numerous research studies have explored this shift of perspective, from person-centric to expansive. How does this occur via observation? Experiencing awe, in most any form, activates the vagus nerve which in turn triggers the parasympathetic nervous system. This activation transports an individual from the fight or flight response to a state of “tend and be-friend”. The vagus nerve, aka “the wanderer” travels from our brain down our spine and to organs in our chest, and abdomen. The vagus nerve can regulate blood pressure, heart rate and breathing rate. It can reduce inflammation, assist digestion, and help mitigate anxiety and depression.

On a cognitive level, awe causes us to question what or why something is happening which can bring about the small-self perspective. Being in a state of awe changes our point of view from ego-centric to altruistic. Recent studies have found we experience a suspension of time when in a state of awe. Everything… slows…down. The human brain can more easily ponder, examine, and appreciate different perspectives. This phenomenon is known as cognitive accommodation.

The beginning of awe is wonder, and the beginning of wisdom is awe. What we cannot comprehend by analysis, we become aware of in awe.

Abraham Joshua Hersche

The influence on well-being

The potential of awe to improve human well-being, mental and physical, is gaining attention. Research has shown that awe can improve relationships through prosocial behavior, loosen the grip of anxiety and depression, and enhance overall quality of life. A specific study out of UC Berkley finds awe produces and sustains feelings of kindness and generosity. In another study, participants were asked to track their moods over several weeks. After experiencing awe two or more times a week the participants reported decreased stress, feeling happier and more satisfied with life in general. Several weeks after the study concluded, participants continued to report positively.

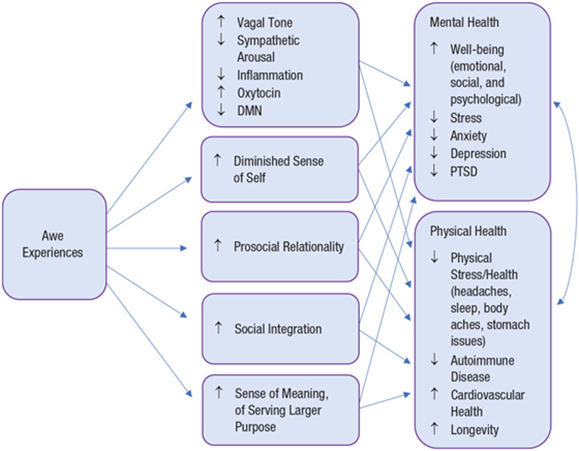

Through the engagement of several processes (diminished sense of self, neurophysiologic change, greater social integration, and elevated sense of meaning) all that utilize awe, result in physical and mental well-being. Acquiring these benefits over time will strengthen the body and engender a sense of connection.

Self-Induced Awe

While Reese Nelson experienced the emotion of awe witnessing an eclipse and spending time in natural environments, he feels strongly that you can easily experience awe in your own backyard. “Self-induced awe” is a term he uses to describe spending time outdoors purposefully seeking experiences that induce the emotion of awe. Many of us may need to give ourselves permission to take awe-inspiring breaks from our daily routines. Breaks that do not require expensive travel or time away from daily responsibilities. Prioritizing time in nature offers the opportunity to come into the present moment and develop your sense of wonder in the beauty that surrounds you. Rachael Carson, marine biologist, and author of Silent Spring, provides excellent advice in an essay written in 1956 titled The Sense of Wonder. Carson encourages us all to “develop a sense of wonder” by using all five senses and to sharpen your observation skills. “One way to open your eyes to unnoticed beauty is to ask yourself the questions, “What if I had never seen this before” and “What if I never see this again”. These words were written almost 70 years ago yet remain meaningful today.

A captivating example of finding awe in your own backyard is the basis for the 2021 documentary, My Garden of a Thousand Bees. During the coronavirus lockdown, in the spring of 2020, Martin Dohrn, an acclaimed wildlife filmmaker, finds inspiration and awe in his own backyard garden in Bristol, England. His documentary exemplifies how close we are to nature and how blind we can be to its very existence.

As horticultural therapy practitioners, better understanding this complex human emotion and embracing the positive power of awe is sure to enhance therapeutic interventions as the mental health benefits are evident, accessible, and sustainable. Coming into a state of awe and experiencing the small-self perspective strengthens connection to one another, the natural world and beyond. This experience benefits participant and practitioner equally. It can occur individually or collectively, in a group setting. Spring will soon evolve into summer and the opportunity to encounter awe in the garden will be abundant!